The inconsistent and shifting language of conversation design

The mystery of the indecipherable design triangle is actually a very real issue. Today, within one conversation design team, a triangle dropped into a flow means something completely different than what it means for designers at another company. Moreover, they often can’t even agree on when or how that triangle should be used, let alone what it means. There’s no reason for that. But it has a cost.

It means that during a collaboration, designers’ flows aren’t mutually intelligible. Each might as well be hieroglyphics. And that’s true within those companies, across teams and departments. Whenever a conversation design leader is hired from somewhere else and brings their preferences, or two teams work in silos, you get compounding inconsistencies.

In the most inconvenient scenarios, you get false positives—instances where one designer thinks they know what another’s triangle means, but is incorrect, and builds a skill upon a faulty assumption.

This raises the cost of onboarding conversation designers and bringing on CxD teams. The payroll platform Gusto puts the cost of replacing a technical worker (measured by being a sole contributor with a high salary, which conversation designers mostly fall into) at $84,000. A large part of that is retraining—teaching them the unique language of that team’s flows.

And the triangle is just one example. Every day at Voiceflow we hear:

- Should conversation designers design the natural language understanding (NLU) bot, or is that the NLU designer’s job?

- Is it “repair path” or “error path”? Can an error path contain repair paths?

- Is it a slot, entity, or variable? What’s the difference?

At Voiceflow, we find ourselves often having to create our own definitions simply to be able to create our product and work on shared understanding. One example of this was defining the six variations we see on the term “context”. You hear about “context” all the time in conversation design, yet it can have wildly different meanings from team to team. In order to build tooling to cover these use cases, we first had to define it ourselves. How many other teams have written their own definition?

We aren’t going to be able to define, share, and encode best practices if we can’t even agree on what the building blocks are called.

Another example of an actual product change to match industry terms, we used to call our entities “slots,” which came from Amazon’s Alexa skill-building lexicon, but have since moved to entities as we saw the industry consolidate on that term. As a toolmaker, it can be difficult to always have the most up-to-date lexicon, as there is no singular institution maintaining a source of truth. It’ll fall to some industry body or collective to agree on and build a true glossary.

Until that happens, unfortunately, lots of the software companies and agencies in this space are actively making it worse—often, unintentionally. In an attempt to trademark features and processes, companies add to the pile of terms with new, proprietary synonyms for things that already have well-accepted names. Seeing product launch posts like this on LinkedIn reminds me of the Scooby Doo meme where underneath the so-called “revolutionary” release is … a decades-old thing with a self-serving twist.

As an industry, we aren’t going to be able to define, share, and encode best practices if we can’t even agree on what the building blocks are called. We can’t talk about good and bad when we’re speaking different languages.

Who’ll provide these standards?

As an industry, we have to commit to building the category, not just our own brands. At Voiceflow, we will provide terms for things we feel aren’t well-named, but, if there is a better, or even just widely used adopted name, we’ll shift our lexicon to match. A rising tide lifts all boats—and ultimately, one of the biggest lifts we can all offer our industry is agreeing on how we describe.

And to anyone out there working on a project to define all this, I’d love to chat. When I think about the ESRO’s lunar landing that never happened, I can’t help but also think about the conversation design industry, and what sort of dreams will go unrealized if we can’t end the mistranslation.

The inconsistent and shifting language of conversation design

The mystery of the indecipherable design triangle is actually a very real issue. Today, within one conversation design team, a triangle dropped into a flow means something completely different than what it means for designers at another company. Moreover, they often can’t even agree on when or how that triangle should be used, let alone what it means. There’s no reason for that. But it has a cost.

It means that during a collaboration, designers’ flows aren’t mutually intelligible. Each might as well be hieroglyphics. And that’s true within those companies, across teams and departments. Whenever a conversation design leader is hired from somewhere else and brings their preferences, or two teams work in silos, you get compounding inconsistencies.

In the most inconvenient scenarios, you get false positives—instances where one designer thinks they know what another’s triangle means, but is incorrect, and builds a skill upon a faulty assumption.

This raises the cost of onboarding conversation designers and bringing on CxD teams. The payroll platform Gusto puts the cost of replacing a technical worker (measured by being a sole contributor with a high salary, which conversation designers mostly fall into) at $84,000. A large part of that is retraining—teaching them the unique language of that team’s flows.

And the triangle is just one example. Every day at Voiceflow we hear:

- Should conversation designers design the natural language understanding (NLU) bot, or is that the NLU designer’s job?

- Is it “repair path” or “error path”? Can an error path contain repair paths?

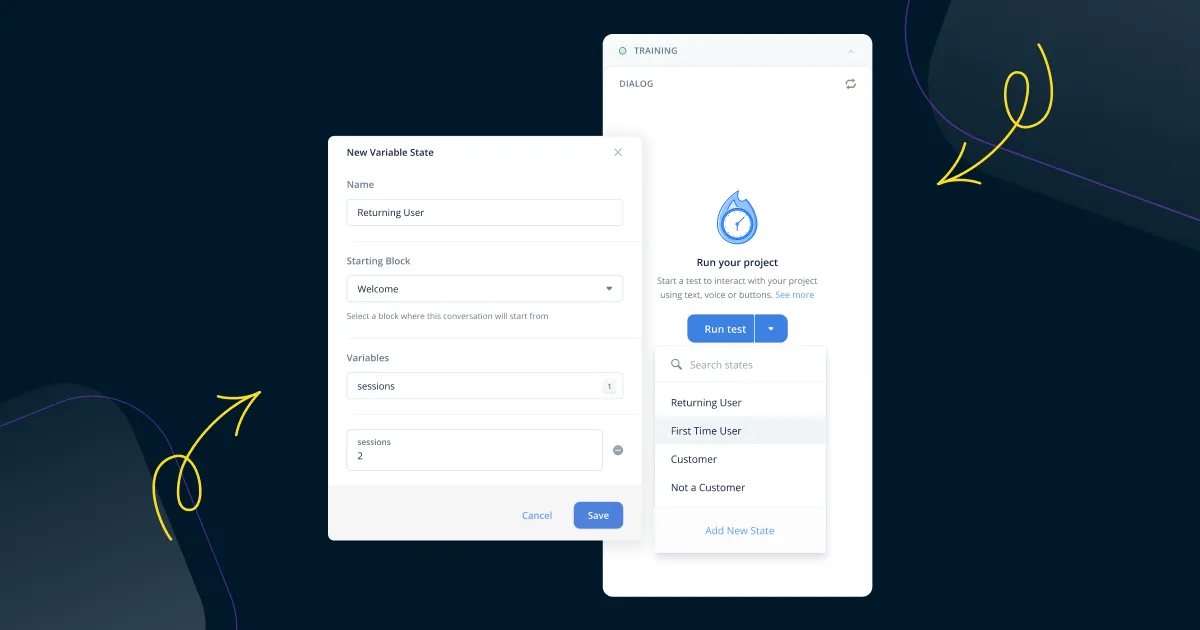

- Is it a slot, entity, or variable? What’s the difference?

At Voiceflow, we find ourselves often having to create our own definitions simply to be able to create our product and work on shared understanding. One example of this was defining the six variations we see on the term “context”. You hear about “context” all the time in conversation design, yet it can have wildly different meanings from team to team. In order to build tooling to cover these use cases, we first had to define it ourselves. How many other teams have written their own definition?

We aren’t going to be able to define, share, and encode best practices if we can’t even agree on what the building blocks are called.

Another example of an actual product change to match industry terms, we used to call our entities “slots,” which came from Amazon’s Alexa skill-building lexicon, but have since moved to entities as we saw the industry consolidate on that term. As a toolmaker, it can be difficult to always have the most up-to-date lexicon, as there is no singular institution maintaining a source of truth. It’ll fall to some industry body or collective to agree on and build a true glossary.

Until that happens, unfortunately, lots of the software companies and agencies in this space are actively making it worse—often, unintentionally. In an attempt to trademark features and processes, companies add to the pile of terms with new, proprietary synonyms for things that already have well-accepted names. Seeing product launch posts like this on LinkedIn reminds me of the Scooby Doo meme where underneath the so-called “revolutionary” release is … a decades-old thing with a self-serving twist.

As an industry, we aren’t going to be able to define, share, and encode best practices if we can’t even agree on what the building blocks are called. We can’t talk about good and bad when we’re speaking different languages.

Who’ll provide these standards?

As an industry, we have to commit to building the category, not just our own brands. At Voiceflow, we will provide terms for things we feel aren’t well-named, but, if there is a better, or even just widely used adopted name, we’ll shift our lexicon to match. A rising tide lifts all boats—and ultimately, one of the biggest lifts we can all offer our industry is agreeing on how we describe.

And to anyone out there working on a project to define all this, I’d love to chat. When I think about the ESRO’s lunar landing that never happened, I can’t help but also think about the conversation design industry, and what sort of dreams will go unrealized if we can’t end the mistranslation.

.svg)